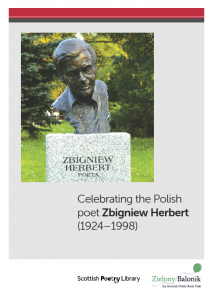

When last year we read Zbigniew Herbert’s Collected Poems 1956–1998 I came across a single reference to Scotland, in the poem ‘The Prayer of the Traveler Mr. Cogito’ or, to give it its Polish title, ‘Modlitwa Pana Cogito – podróżnika’. Here is the relevant section in the Polish original, followed by Alissa Valles’s translation from Collected Poems.

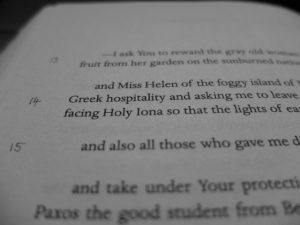

a także Miss Helen z mglistej wysepki Mull na Hebrydach za to że przyjęła mnie po grecku i prosiła żeby w nocy zostawić w oknie wychodzącym na Holy Iona zapaloną lampę aby światła ziemi pozdrawiały się

and Miss Helen of the foggy island of Mull in the Hebrides for offering Greek hospitality and asking me to leave a lamp lit at night in the window facing Holy Iona so that the lights of earth would greet each other

The poem is taken from Herbert’s 1983 collection Raport z oblężonego Miasta / Report from a Besieged City. I was curious to know more about the time he spent in Scotland, which was in fact twenty years before this collection appeared, in autumn 1963. According to Andrzej Franaszek’s 2018 biography of Herbert, using public transport Herbert travelled north from London, stopping in Leeds, York and Durham before arriving in Scotland, where he visited Edinburgh, Aberdeen, Inverness, Oban, Mull and Glasgow, before returning via Carlisle to London.

Franaszek quotes from a postcard Herbert sent from Edinburgh on 18 October:

Wdrapałem się na górę koło Edynburga i oczywiście spadłem trochę (niegroźnie). Tak trzeba. Ziemio ty moja szkocka ukochana! Jutro jadę, ale dobrze nie wiem dokąd. Dziś w nocy narada sztabu z mapą. Jestem bardzo szczęśliwy, żeście mnie wypchnęli w świat. (…) Przede mną góry i skały, kozice i georginie. Naprzód! Hej!!!

I scrambled my way onto a mountain near Edinburgh and I fell down a little (not dangerously). Maybe a good thing. My beloved Scottish earth! I am leaving tomorrow, even though I’m not sure where I’m going. Tonight there will be a conference of the High Command over the map. I’m very glad that you pushed me out into the world. (…) Ahead of me mountains and cliffs, mountain goats and dahlias. Onwards! Hey!!!

In another postcard, sent from Inverness, he described his mixed feelings about the country: he was ‘exhausted but happy, head over heels in love with Scotland; its beauty exhilarates the tourist. But life without sex… one has to go back.’

He returned via the west coast and, finding himself in Oban, decided to cross to the nearby Isle of Mull and from cross there to Iona or, as he consistently called it, using the English adjective, Holy Iona. ‘Holy Iona, czyli kartka z podróży’ (‘Holy Iona, or a page of travel’) was written in 1966 for the West German radio station WDR, and published posthumously in the collection Mistrz z Delft (2008). Of his perspective of islands, he wrote:

Wyspy nie należą do krajobrazu mego dzieciństwa. Urodziłem się w środkowej Europie, w połowie drogi między Morzem Bałtyckim a Czarnym. Pejzaż mojej młodości to podlwowskie okolice: jary i łagodne pagórki porośnięte sosną, na której najpiękniej kwitnie pierwszy sypki śnieg. Morze było tam czymś niewyobrażalnym, a wyspy miały posmak baśni.

Islands were not part of the landscape of my childhood. I was born in Central Europe, halfway between the Baltic and the Black Sea. The landscape of my youth was the area near Lwów, crevices and gentles hills covered in pine on which the first dry snow bloomed beautifully. The sea was something unimaginable there, and islands had a scent of fairytales.

The crossing to Iona had something otherwordly about it. It was 29 October, his birthday, and the ferry was no longer sailing. The landlady of his B&B at Fionnphort phoned a local fisherman, who agreed to take Herbert on the short crossing. In his radio talk he described their meeting-place:

Zimny, wilgotny, siwy ranek. Stoję w pobliżu jetty, która jest po prostu betonową ścieżką wchodzącą w morze. Ocean jest wzburzony, wysokie fale rozbijają się na skałach urwistego brzegu. Nagle z mgły wyłania się mała łódka rybacka płynąca w moim kierunku. Było to jak podanie ręki marzeniu.

A cold, damp, gray morning. I am standing near a jetty, which is just a concrete path going into the sea… which was stormy, high waves crashing against a rocky coast. A small open boat appeared from out of the mist; it was like extending your hand to a dream.

Once on Iona, Herbert explored the recently rebuilt abbey complex. He was particularly struck by his encounter with a sculpture, Descent of the Spirit’, by the Lithuanian-born Jewish sculptor Jacques (Jacob) Lipschitz (1891–1973), who fled France for the USA in 1940.

Photo: William Marnoch, Iona Abbey, 2008

Its inscription, in French, reads:

Jacob Lipchitz juif fidéle à la fonde ses ancêtres a fait cette vierge pour la bonne entente des hommes sur la terre afin que l’esprit régne

Jacob Lipschitz a Jew faithful to the heritage of his ancestors made this virgin for the accord of men on earth so the spirit might reign

Herbert, who had witnessed the destruction of Polish Jewry during the Second World War, appreciated the paradox of recovering signs of community in this, to him, remote place. He expressed gratitude to ‘the Jewish artist who had heard so many words of hatred and responded by reaching for the words of reconciliation’.

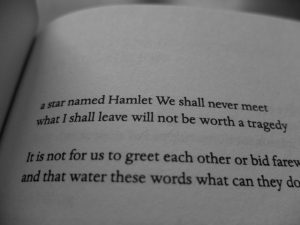

Herbert returned to Mull, and the Fionnphort B&B, that same day. The evening brought him the image of light which he later incorporated into the ‘Prayer’:

Po kolacji gospodyni prosiła mnie, abym postawił małą lampkę w oknie wychodzącym na Holy Iona. Taki jest zwyczaj. Nocą światła obu wysp rozmawiają ze sobą. (…) Nie wiadomo, co przyniesie przyszłość i jak długo trwać będzie rozdarcie świata. Ale dopóki w jedną bodaj noc roku światła tej ziemi będą się pozdrawiały, niecała chyba nadzieja jest pogrzebana.

After supper the landlady asked me to put a small lamp in the window overlooking Holy Iona. That is the custom. At night the lights of both islands talk to each other. (…) It is not known what the future will bring and how long it might be until the world is torn apart, but as long as one night of the year, the lights of this land will offer greetings, hope is not buried.’

*

My thanks to Robin Connelly, Grażyna Fremi, Michał Kuźmiński, Basia Macmillan and Robert Macmillan for their help in sourcing and translating material on Herbert’s trip. As well as the books mentioned above, online there is, in Polish, a useful article from 2007 by Piotr Toczynski about Herbert and Iona, and a recording of Herberttalking about Scotland (scroll down to the heading ‘Szkocja’).