Nobody Leaves (2017)

Regarded as a central part of Kapuściński’s work, these vivid portraits of life in the depths of Poland embody the young writer’s mastery of literary reportage

When the great Ryszard Kapuściński was a young journalist in the early 1960s, he was sent to the farthest reaches of his native Poland between foreign assignments. The resulting pieces brought together in this new collection, nearly all of which are translated into English for the first time, reveal a place just as strange as the distant lands he visited.

From forgotten villages to collective farms, Kapuściński explores a Poland that is post-Stalinist but still Communist; a country on the edge of modernity. He encounters those for whom the promises of rising living standards never worked out as planned, those who would have been misfits under any political system, those tied to the land and those dreaming of escape.

Buy online:

Zielony Balonik book club notes:

Stuart recalled his first visit to Poland around the time Kapuściński was writing these pieces: living in a cramped house, sitting in a Volkswagen being driven very slowly to avoid the many potholes in the road, the use of slang and dialect.

Jenny noted that the Penguin edition is a translation of the original Polish edition (1962); later Polish editions include more pieces, including a fine essay in which Kapuściński writes of his childhood during the war, ‘Exercises in Memory’. In it shoes become a symbol of power and authority – as a child he has no shoes, or only poor home-made ones, and he compares these to the boots worn by Gestapo officers. The war never really goes away.

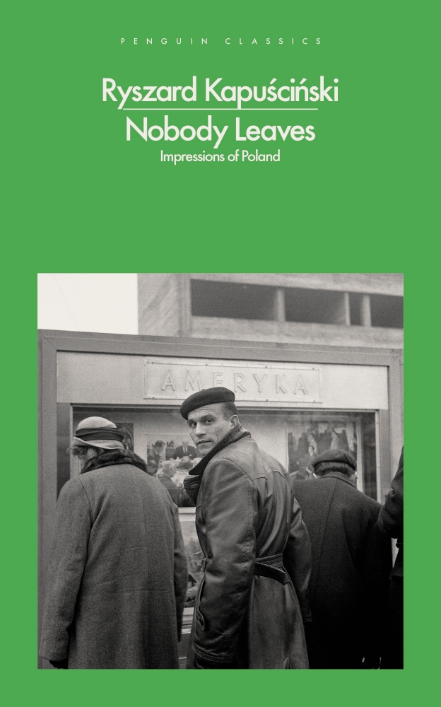

The Polish edition is called Busz po polsku, literally The Polish Bush or The Polish Jungle. The cover of the Penguin edition seems misleading, with the title Nobody Leaves above a photograph of a group of people looking towards a display beneath the word ‘AMERYKA’; in fact the piece entitled ‘Nobody Leaves’ is a claustrophobic family drama which could play out in many societies.

Zenon wondered how much of the book was fiction. He felt it played with ideas of truth and fiction, but not very well. He considered pieces, especially ‘The Taking of Elżbieta’, were propaganda for the regime, and bemoaned the lack of any sympathy for Elżbieta as a nun. It was known Kapuściński wrote more bombastic news items alongside the kind of quirky stories included here.

Ewa said Kapuściński’s work had been popular in the Netherlands. She thought the book had been well translated into English.

There were many characters in the book Krystyna could recognise. She compared Kapuściński’s work to that of Feargal Keane.

Grażyna had a complementary Polish book including Kapuściński’s photographs of the time. Kapuściński wrote for the publication Polityka, which after 1956 employed writers who had been previously banned. He writes of rural, provincial life, where Warsaw never mind the USA is unimaginably distant. In Poland it wasn’t communism but capitalism which collectivised the land, ie gathered together smallholdings into larger units.

Bob mentioned Domosławski’s biography, which revealed how Kapuściński had co-operated with the Communist authorities and gave details of his extra-marital affairs, as well as investigating the veracity of his reportage. (The Guardian in a review admired the book’s nuanced approach to its subject.)